Basic examples of formal verification in Engee

This article provides basic examples of formal model verification, demonstrating the practical use of LTL specifications in Spin and the interpretation of the results obtained.

Example 1

Block Chart models promela_a.engee contains a single state A.

Find out if the status is active A or not, it is possible by the value of a global variable. promela_a_S.Chart.state.A.is_active in the generated file promela_a.pml.

The activity of Chart can also be judged by the value of the global variable promela_a_S.Chart.state.is_active.

Using the preprocessor, we will assign abbreviated aliases to these variables for use in the formulas of the specification.:

#define a promela_a_S.Chart.state.A.is_active

#define chart promela_a_S.Chart.state.is_activeand we’ll add them along with the specifications.:

// состояние "A" не активно в начальный момент времени:

ltl spec1 { !a }

// состояние "A" обязано стать активным в начальный момент времени или когда-нибудь в будущем:

ltl spec2 { <>a }

// блок Chart не активен в начальный момент времени:

ltl spec3 { !chart }

// активность состояния "A" и блока Chart изменяется синхронно:

ltl spec4 { [] (chart == a) }to the end of the file promela_a.pml.

We will verify the specifications:

$ spin -run -ltl spec1 promela_a.pml 2>&1 | grep errors:

State-vector 40 byte, depth reached 0, errors: 0

$ spin -run -ltl spec2 promela_a.pml 2>&1 | grep errors:

State-vector 40 byte, depth reached 6, errors: 0

$ spin -run -ltl spec3 promela_a.pml 2>&1 | grep errors:

State-vector 40 byte, depth reached 0, errors: 0

$ spin -run -ltl spec4 promela_a.pml 2>&1 | grep errors:

State-vector 40 byte, depth reached 12, errors: 0The console output of the Spin program shows that each of the specifications is being fulfilled — the verification was successful.

Example 2

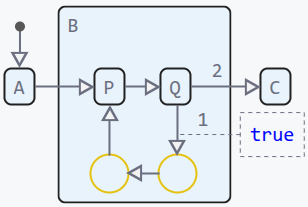

Model abcpq.engee in the figure has three features:

-

The endless loop

P→Q→P→ …; -

An unreachable state

C; -

Deadlock state

B.

Let’s try to verify these statements.

As usual, we will declare abbreviated aliases for variables that determine the activity of our states. To do this, add to the file abcpq.pml the macro section of the preprocessor:

#define a abcpq_S.Chart.state.A.is_active

#define b abcpq_S.Chart.state.B.is_active

#define c abcpq_S.Chart.state.C.is_active

#define p abcpq_S.Chart.state.B.P.is_active

#define q abcpq_S.Chart.state.B.Q.is_activeSpecify the unreachability of the state C you can use the formula "always don’t `C`", the verification of which, as expected, is successful:

ltl spec1 { []!c } // состояние C недостижимоThis specification can be considered a property of safety (safety) □p for the formula p, forbidding the condition C activate (that is p = ¬C).

However, if you replace the name in the formula above c on q:

ltl absurd2 { []!q } // утверждается (неверно), что Q никогда не станет активнымverification of the modified formula is expected to result in an error, since it was initially obvious that the condition Q achievable:

$ spin -run -ltl absurd2 abcpq.pml

pan: ltl formula absurd2

pan:1: assertion violated !( !( !(abcpq_S.Chart.state.B.Q.is_active))) (at depth 49)

pan: wrote abcpq.pml.trail

...

State-vector 64 byte, depth reached 49, errors: 1

...A counterexample obtained from the trace file:

$ spin -t -p -k abcpq.pml.trail abcpq.pmlwhere should I pay attention to the string indicating the assignment, which, according to the specification, should not be:

42: proc 0 (fsm:1) abcpq.pml:114 (state 34) [abcpq_S.Chart.state.B.Q.is_active = 1]and a string with a variable value that contradicts the specification at the end of the trace.:

abcpq_S.Chart.state.B.Q.is_active = 1Now let’s check the property of liveliness (liveness) — the need to ever become active:

ltl absurd3 { <>c } // утверждается, что C рано или поздно станет активнымVerification result:

$ spin -run -ltl absurd3 abcpq.pml

...

pan: ltl formula absurd3

pan:1: acceptance cycle (at depth 31)

pan: wrote abcpq.pml.trail

...

State-vector 56 byte, depth reached 65, errors: 1

...Here, investigating the route is ineffective: the counterexample is obviously endless.

And here are the properties of liveliness ◊A ∧ ◊B ∧ ◊P ∧ ◊Q the remaining states are verified successfully.:

ltl spec4 { (<>a) && (<>b) && (<>p) && (<>q) } // свойство живости состояний A, B, P и QYou can also use LTL to verify the fairness property. □◊P or □◊Q that is, the requirement that the event (activation of P or Q) will occur infinitely often:

ltl spec5 { []<>p } // свойство справедливости P

ltl spec6 { []<>q } // свойство справедливости Qand the stabilization property (stabilization) ◊□B — the requirement that some event (deadlock B activity) will sooner or later occur forever:

ltl spec7 { <>[]b } // свойство стабилизации BUsing the implication and the exclusive "OR", it is possible to specify the correlation of activity of the parent and child states.:

ltl spec8 { [](b -> (p ^ q)) } // если активно родительское состояние, то активно и одно из дочернихAn equivalence relation can be used instead of an implication.:

ltl spec9 { [](b <-> (p ^ q)) } // родительское состояние активно тогда и только тогда, когда активно одно из дочернихCombining the implication and the operator neXt, you can make sure that the activity states P and Q oscillates with a frequency of 1 step:

ltl spec10 { []((p -> X q) && (q -> X p)) } // за активацией состояния P всегда следует активация Q и наоборотExample 3

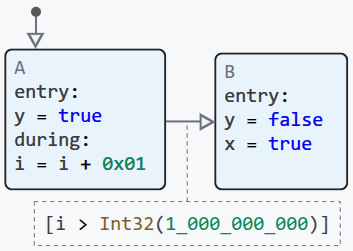

Let’s consider another simple model ab.engee, the verification of the properties of which in the direct simulation mode can take a considerable time, whereas the formal verification of the same properties is performed almost instantly.

Transition between states A and B is executed after the variable i it will increase a billion times.

Let’s announce the abbreviated names:

#define chart ab_S.Chart.state.is_active

#define a ab_S.Chart.state.A.is_active

#define b ab_S.Chart.state.B.is_active

#define i ab_S.Chart.locals.i

#define x ab_S.Chart.output.x

#define y ab_S.Chart.output.yA formula verifying the fact of a mandatory transition between states A and B Sometime in the future:

ltl spec1 { <>(a -> X b) }Let’s make sure that this transition cannot occur at every step; a stronger specification will lead to an error.:

ltl absurd2 { [](a -> X b) } // неверно!Operator until it is also being successfully verified "sometime in the future":

ltl spec3 { <>(a U b) }Considering that the operator becomes true immediately after activating the Chart block, it can be written more strictly:

ltl spec4 { [](!chart || (a U b)) }Or equivalent, but shorter:

ltl spec5 { [](chart -> (a U b)) }The weaker form is also successfully verified.:

ltl spec6 { [](chart -> (a W b)) }And the "liberation" operator (release) leads to an error because the states A and B they cannot be active at the same time:

ltl absurd7 { [](chart -> (a V b)) } // неверно!Let’s check the same properties using the values of the output variables of the Chart block. x and y, originally installed in false:

ltl spec8 { <>(y U x) }

ltl spec9 { [](chart -> (y U x)) }

ltl spec10 { [](chart -> (y W x)) }

ltl absurd11 { [](chart -> (y V x)) } // неверно!And finally, let’s check the range of values of the variable. i.

At the initial time, the value of the variable i equally 0:

ltl spec12 { i == 0 }Meaning i It always lies in the range [0..1000000001]:

ltl spec13 { [](0 <= i && i <= 1000000001) }Ever i takes its maximum value 1000000001:

ltl spec14 { <>(i == 1000000001) }