We are modeling the first artificial satellite of the Earth

In this project, we will build the ground track of the PS-1 satellite, launched on October 4, 1957.

Preparation and launch

Let's get ready for work: open the coast contour map and set the desired projection for it.

Pkg.add(["SatelliteToolbox", "Shapefile", "Proj"])

We downloaded the map from the [Natural Earth] repository in advance (https://www.naturalearthdata.com /). You will find more extensive information for working with maps here.

using Shapefile, Downloads, Proj

shp_path = joinpath(@__DIR__, "map", "ne_110m_coastline.shp");

table = Shapefile.Table(shp_path);

trans = Proj.Transformation("+proj=longlat", "+proj=robin +lon_0=0 +x_0=0 +y_0=0");

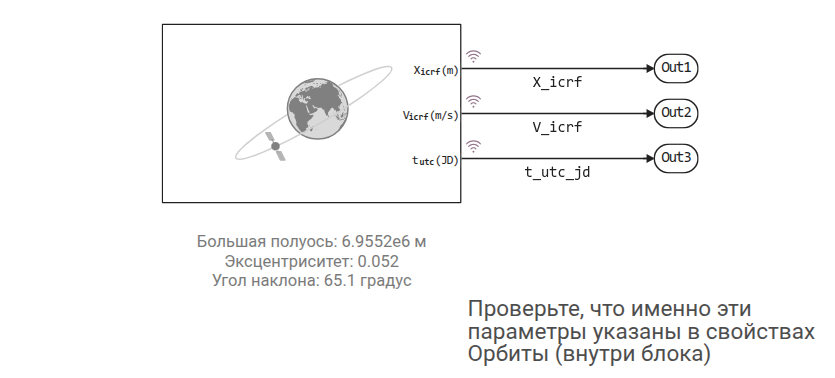

Now let's run the model. We will get several state vectors.

engee.open("sputnik_model.engee") # Please comment if the model is already open.

data = engee.run("sputnik_model")

X_icrf = collect(data["X_icrf"]).value;

V_icrf = collect(data["V_icrf"]).value;

t_utc_jd = collect(data["t_utc_jd"]).value;

df = DataFrame( time = data["X_icrf"].time, t_utc_jd = t_utc_jd, X_icrf = X_icrf, V_icrf = V_icrf);

We have assembled the vectors into a DataFrame object, now we will fill it with additional parameters.

Translating coordinates to other systems

To display graphs, it is usually interesting to translate coordinates into a geocentric and geodetic system. Consider the following considerations:

-

for our project, the ICRF system is almost identical to the GCRF (ECI) system, with errors of the order of one meter

-

the observer will be located in Moscow

-

topocentric coordinates are plotted using the WGS84 ellipsoid

using DataFrames

using SatelliteToolbox

using LinearAlgebra

# Where is the observer located

OBS_LLA = [deg2rad(55.7558), deg2rad(37.6173), 0.2e3]

eop = fetch_iers_eop()

# Adding new columns

df[!, :lon] = zeros(length(df[!, :time]))

df[!, :lat] = zeros(length(df[!, :time]))

df[!, :alt] = zeros(length(df[!, :time]))

df[!, :az] = zeros(length(df[!, :time]))

df[!, :el] = zeros(length(df[!, :time]))

df[!, :range] = zeros(length(df[!, :time]))

# The parameters of the Earth for converting the coordinates of the observer

a = 6378137.0

lat_obs, lon_obs, alt_obs = OBS_LLA

x_obs = (a + alt_obs) * cos(lat_obs) * cos(lon_obs)

y_obs = (a + alt_obs) * cos(lat_obs) * sin(lon_obs)

z_obs = (a + alt_obs) * sin(lat_obs)

for i in 1:length(df[!, :time])

# ICRF → ITRF conversion

sv_icrf = OrbitStateVector(df[i, :t_utc_jd], df[i, :X_icrf], df[i, :V_icrf])

sv_ecef = sv_eci_to_ecef(sv_icrf, GCRF(), ITRF(), df[i, :t_utc_jd], eop)

# Geodetic coordinates

lat, lon, alt = ecef_to_geodetic(sv_ecef.r)

df[i, :lon] = rad2deg(lon)

df[i, :lat] = rad2deg(lat)

df[i, :alt] = alt

# Topocentric coordinates

Δr = sv_ecef.r - [x_obs, y_obs, z_obs]

range_val = norm(Δr)

# ENU coordinates (Local coordinate system of the observer east-north-top)

e = -sin(lon_obs)*Δr[1] + cos(lon_obs)*Δr[2]

n = -sin(lat_obs)*cos(lon_obs)*Δr[1] - sin(lat_obs)*sin(lon_obs)*Δr[2] + cos(lat_obs)*Δr[3]

u = cos(lat_obs)*cos(lon_obs)*Δr[1] + cos(lat_obs)*sin(lon_obs)*Δr[2] + sin(lat_obs)*Δr[3]

az = atan(e, n) % (2π)

el = atan(u, sqrt(e^2 + n^2))

df[i, :az] = rad2deg(az)

df[i, :el] = rad2deg(el)

df[i, :range] = range_val

end

Graph of the Earth's trajectory of the spacecraft

The obtained geodetic coordinates can simply be plotted, but in order for them to be plotted as lines, you first need to divide each circle around the planet into separate segments so as not to observe unnecessary jumps on the graph (between longitude 180 and -180).

ground_track_df = select(df, [:lon, :lat, :time])

# The ground route of the orbit

ground_track_lons = df.lon

ground_track_lats = df.lat

# We divide it into segments

jumps = findall(i -> abs(ground_track_lons[i+1] - ground_track_lons[i]) > 180, 1:length(ground_track_lons)-1)

segments = []

start_idx = 1

for jump_idx in jumps

push!(segments, (ground_track_lons[start_idx:jump_idx], ground_track_lats[start_idx:jump_idx]))

start_idx = jump_idx + 1

end

# Adding the last segment

push!(segments, (ground_track_lons[start_idx:end], ground_track_lats[start_idx:end]))

# We draw each segment separately

plot(title="The ground route of the orbit")

for (seg_lons, seg_lats) in segments

xy_transf = trans.(seg_lons, seg_lats)

xx,yy = getindex.(xy_transf, 1), getindex.(xy_transf, 2)

plot!(xx, yy, legend=false, linecolor=:blue)

end

plot!()

for shape in table

x = [point.x for point in shape.geometry.points]

y = [point.y for point in shape.geometry.points]

xy_transf = trans.(x, y)

xx,yy = getindex.(xy_transf, 1), getindex.(xy_transf, 2)

plot!(xx, yy, c=1, lw=0.5, fill=:lightblue)

end

plot!()

Graph of satellite observability from the Earth's surface

To plot the satellite's observability from the point where the observer is located, we calculated the topocentric azimuth and declination. We will separate only those segments of the trajectory when the satellite was above the horizon.

# Points above the horizon

skyplot_mask = df.el .> 0

skyplot_az = df.az # df.az[skyplot_mask] # This data can already be deduced

skyplot_el = df.el # df.el[skyplot_mask] # but let's divide them into segments

true_indices = findall(skyplot_mask) # We divide it into continuous segments

gaps = findall(diff(true_indices) .> 1) # We find gaps in the indexes

boundaries = vcat([1], gaps .+ 1, [length(true_indices) + 1]) # Segment boundaries

segments_az = Vector{Vector{eltype(skyplot_az)}}()

segments_el = Vector{Vector{eltype(skyplot_el)}}()

for i in 1:length(boundaries)-1

start_idx = boundaries[i]

end_idx = boundaries[i+1] - 1

segment_indices = true_indices[start_idx:end_idx]

push!(segments_az, skyplot_az[segment_indices])

push!(segments_el, skyplot_el[segment_indices])

end

In a separate cell, we will display a hemisphere and plot all the segments on it in order to see the trajectory of the satellite as it was seen from the surface of the Earth.

# Creating a hemisphere

n = 30

u = range(0, 2π; length=n)

v = range(0, π/2; length=n)

x_sphere = cos.(u) .* sin.(v)'

y_sphere = sin.(u) .* sin.(v)'

z_sphere = ones(n) .* cos.(v)'

# Drawing a hemisphere

surface(x_sphere, y_sphere, z_sphere, alpha=0.4, legend=false)

xlabel!("East"); ylabel!("North"); zlabel!("Top")

# Drawing trajectory segments

for (azimuths,elevations) in zip(segments_az, segments_el)

# Convert to Cartesian coordinates

az_rad = deg2rad.(azimuths)

el_rad = deg2rad.(elevations)

x = cos.(el_rad) .* cos.(az_rad)

y = cos.(el_rad) .* sin.(az_rad)

z = sin.(el_rad)

plot!(x, y, z, lw=4)

end

plot!(legend=false, title="Satellite visibility chart (Moscow)")

We can see when and how the satellite was observed from a point in Moscow. And since the satellite's state vector also includes velocity, we can calculate the Doppler shift and specify exactly how its signal sounded, calling us to new achievements.

Conclusion

We obtained the coordinates of the PS-1 satellite during 60,000 seconds of observation (the real satellite spent about 8 million seconds in orbit) and built a couple of useful graphs to interpret the trajectory of this spacecraft.