Regression using a neural network (a minimal example)

In this example, we will discuss what minimum operations allows you to train a fully connected neural network * (fully-connected, FC)* regression problem.

Task description

Let's train the most classical type of neural networks to "predict" the value of some one-dimensional function. Our goal is to create the simplest algorithm, which we will later complicate * (and not vice versa)*.

Pkg.add(["Flux"])

# @markdown ## Configuring neural network parameters

# @markdown *(double click allows you to hide the code)*

# @markdown

Параметры_по_умолчанию = false # @param {type: "boolean"}

if Parameters_to Silence

Learning rate coefficient = 0.01

Number of Training cycles = 100

else

Количество_циклов_обучения = 80 # @param {type:"slider", min:1, max:150, step:1}

Коэффициент_скорость_обучения = 0.1 # @param {type:"slider", min:0.001, max:0.5, step:0.001}

end

epochs = Number of Training Cycles;

learning_rate = Coefficient of learning rate;

using Flux

Xs = Float32.( 0:0.1:10 ); # Generating training data

Ys = Float32.( Xs .+ 2 .* rand(length(Xs)) ); # <- expected output from the neural network

data = [(Xs', Ys')]; # In this format, the data is passed to the loss function.

model = Dense( 1 => 1 ) # Neural network architecture: one FC layer

opt_state = Flux.setup( Adam( learning_rate ), model ); # Optimization algorithm

for i in 1:epochs

Flux.train!( model, data, opt_state) do m, x, y

Flux.mse( m(x), y ) # Loss function - error on each element of the dataset

end

end

X_прогноз = [ [x] for x in Xs ] # The neural network accepts vectors, even if we have a function of one argument.

Y_прогноз = model.( X_прогноз ) # For each [x], the neural network calculates for us [y]

gr() # We have obtained a "vector of vectors", which we transform to display on the graph.

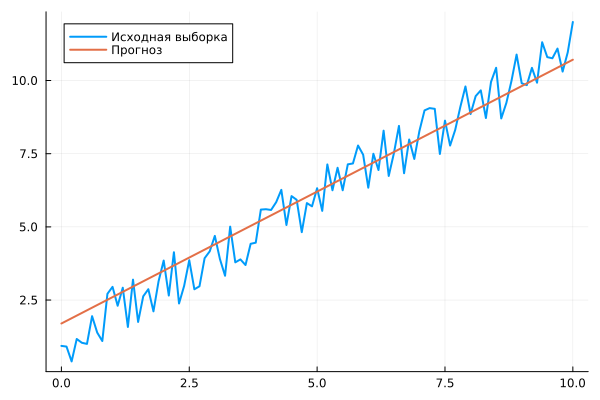

plot( Xs, Ys, label="Initial selection", legend=:topleft, lw=2 )

plot!( Xs, vec(hcat(Y_прогноз...)), label="Forecast", lw=2 )

Change the parameters of the learning process and restart the cell using the to evaluate how changing the settings will affect the forecast quality.

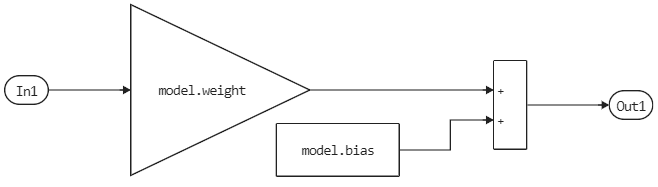

Creating a neural network in the form of blocks on a canvas

Our neural network has such a simple structure that it is very easy to transfer it to the canvas and use it in our own library of blocks.

👉 This model can be run independently of the script. The "callbacks" of the model contain all the code for training the neural network, so when opening the file for the first time

neural_regression_simple.engeeif the variablemodelit doesn't exist yet, the neural network is being trained anew.

The model can be easily assembled from blocks in the workspace. It gets parameters from the variables workspace, but they can be entered into the properties of these blocks as fixed matrices and vectors.

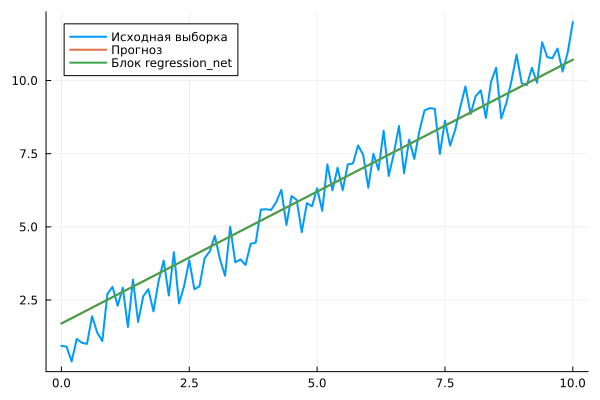

Let's run this model and compare the results.:

if "neural_regression_simple" ∉ getfield.(engee.get_all_models(), :name)

engee.load( "$(@__DIR__)/neural_regression_simple.engee");

end

data = engee.run( "neural_regression_simple" );

# Since all operations in the model are matrix-based, we again have to "smooth out" the Y variable.

plot!( data["Y"].time, vec(hcat(data["Y"].value...)), label="The regression_net block", lw=2 )

If the structure of the diagram is identical to the structure of the neural network, then the results of the runs "from the code" and "from the canvas" will also be identical.

Usually, the structure of a neural network changes less frequently than the data set and the task statement. Therefore, it is quite possible to model the structure twice: first in code, then in the form of graphic blocks on a canvas.

Explanation of the code

Let's review our short code and comment on interesting points.

We use Float32 Instead of Float64, which is used by default in Julia (everything will work without it, but the library Flux it will issue a one-time warning).

Xs = Float32.( 0:0.1:10 );

Ys = Float32.(Xs .+ 2 .* rand(length(Xs)));

Accuracy Float32 It is more than enough for neural networks, their prediction errors usually exceed the rounding error due to the coarser bit grid. In addition, execution on the GPU, when we get to it, is faster with this type of data.

The data will be fed to the loss function via an iterator. There should be tuples inside the dataset (Tuple) with data columns - one column of inputs, one column of outputs. There are several other ways to submit data, for now we will focus on the one below.

data = [(Xs', Ys')];

A neural network consists of a single element – a linear combination of inputs and weights with the addition of offsets (* without an activation function, or, equivalently, with a linear activation function*). We didn't even begin to surround the object. Dense by design Chain(), which is usually used to create multi-layered neural networks * (although both networks work the same way)*.

model = Dense( 1 => 1 )

Let's set up the Adam optimization algorithm (Adaptive Moment Estimation), one of the most effective optimization algorithms in neural network training. The only parameter that we pass to him is the learning rate coefficient.

opt_state = Flux.setup( Adam( learning_rate ), model_cpu )

Now it's time to train the model. We perform a certain number of repeated passes through the sample, calculate the loss function and adjust all the variables of the neural network in the direction of reducing the error gradient.

Loss function (loss function) is the only place where the model is explicitly executed during training. It is usually expressed in terms of the sum of errors on each data element (the sum of cost functions). Here we simply use the standard mean squared error function (mean squared error, MSE) from the Flux library.

for i in 1:epochs

Flux.train!(model, data, opt_state) do m, x, y

Flux.mse( m(x), y )

end

end

It remains to use the trained model. We will pass input data to it as to a function and get output forecasts.

Y_прогноз = model.( X_прогноз )

X_прогноз = [ [x] for x in Xs ]

Conclusion

It took us 10 lines of code to generate the data and train the neural network, and 5 more to display its forecasts on a graph. Small changes will make the neural network multi-layered or train it on data from the XLSX table.

We found that after training, it is quite easy to transfer the neural network to the canvas and use it as another block in the system diagram, and with sufficient simplification of the scheme, even generate C code from it. In this way, we can ensure an end–to-end system update process, from data sampling to the controller.